(Text of an Interview Published by TELL Magazine,

August 31, 1998, No. 35 pp10-24.)

Ayo Obe wrote of this lengthy interview: "Food for Thought" She said of it, "it . . . bears reading and thinking about. It's not pleasant."

Adapted from Association of Nigerian Scholars for Dialogue, ANSD publication on www.nigerianscholars.africanqueen.com

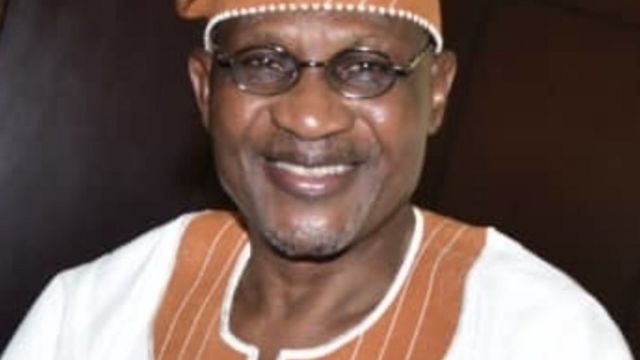

Professor Olufemi Odekunle has spent his entire career studying criminals and the raw materials that spur them within society. He sits often in the relative comfort of his office and pays short clinical visits to prisons. Then in 1994, he got a job in Abuja, the nation's seat of power as the chairman, Advisory Committee to the Chief of General Staff, CGS, on Socio-Political and Economic Matters. He wrote papers. He lectured others in a professorial manner. He learnt a lot about criminality and its influence in the seat of power. He fought the subtle abuse of power; he rode with the powerful and mighty. He almost believed he was just doing his job until the wee hours of one Saturday last December.

Odekunle slept late on December 20, 1997, for he was preparing to go home for the long Christmas holiday. Everything was packed and the children were back home from schools, including two teenage sons and a teenage daughter. Ilesa, Osun State, where Odekunle was born 56 years ago, would be sweet, he must have thought. After 12 years of trying, he had just completed his country house. Then crime came crashing into the sanctity of Odekunle's home. At 3 a.m., plain-clothes members of the Strike Force forced down the door of Odekunle's Abuja home and seized him from his matrimonial bed. He was beaten blue and black in front of his wife and wailing children. The children, including a toddler, were detained in the house for many months while the head of the family went to hell. The invaders not only arrested Odekunle, they arrested his three cars, including two private ones, all his personal documents, his passports, his children's birth certificates, his educational certificates and his share certificates. The invaders simply decided to clean him out believing that the professor was on a journey of no return.

Now, Odekunle is back to tell his story. He was an inner player in the bitter struggle within Aso Rock battlement until the blood-curdling climax last December when Odekunle, along with general Oladipo Diya and many top military officers and civilians, were arrested for allegedly plotting to topple the evil regime of General Sani Abacha. A graduate of the University of Ibadan, 1968, he got his Ph.D. in sociology and social psychiatry from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in the United States in 1974. He has worked at the Ahmadu Bello University, ABU, Zaria, the intellectual power house of the old North since 1970. There, he collided with what he called "The Northern oligarchy." His clinical training under the wings of the famous Professor Adeoye Lambo must have forewarned him about the danger of his Aso Rock adventure.

Now that he is free from the horror of the arrest, the torture in the Aso Rock chambers of the devil, the trauma of the trial before a secret military tribunal, the nightmare of the Jos prisons, and the agony of his family, he believed his is duty-bound to tell Nigerians the story from the valley of death. He spoke about the inside working of the Abacha presidency, the story of the arrest and trial of Diya and company, the all-pervading influence of the Northern oligarchy, the need for a restructured federation if Nigeria is to survive and the danger of dictatorship. He spoke for two days with Dele Omotunde, TELL's deputy editor-in-chief and Dare Babarinsa, executive editor at his Ilesa country house. The interview, both a confession and a narration, was also a catharsis. Excerpts:-

Professor Odekunle, we welcome you back from detention after all these days. On behalf of TELL magazine, we congratulate you on your release and for coming back home alive. Could you tell us what you have gone through? How the news of your release came about, did it come as a surprise and what exactly was your immediate reaction?

You'll recall that the judgment of the Special Military Tribunal, SMT, was given on April 28 and we had expected by that verdict, to be released that same day or the next day. But from one day it became two days, then from days to weeks and later months. thus, expecting to be released was a daily affair. Now, when you asked me whether it came as a surprise, I'd say it didn't come as a surprise, yet it came suddenly because we were always kept in the dark as to what was going to happen. Anyway, to answer your question, I'd say I was surprised though at the same time, I was expecting that one day they would eventually come to effect the tribunal's judgment. At the same time, we were expecting that the cases of those sentenced would be reviewed by the PRC. The information at the time was that the PRC had not met. But as far as we were concerned, those of us discharged and acquitted had no business with the PRC since the convening letter stated clearly that only those who were sentenced would still have their cases reviewed by the PRC and the judge advocate - the lawyer assisting the tribunal - had stated that those who were discharged and acquitted were free "right from this courtroom." So we had been expecting that we would be released but it [the release] never came ... Since that April 28, it had been a waiting game. So, this particular day they just came about 10.30 p.m. or so and said "Prof., pack your load."

What date exactly were you set free?

July 15 [1998]. I think it was a [Wednesday] around 10.30 p.m. when Major Mumuni and others came and woke us up. We were led from the ward to the prison comptroller's office where they called out our names. After the roll-call, they took us to the Rukuba Barracks where we slept for the night, in the officer's mess.

So, these other people who were with you in Jos, I mean those who were freed, how many were you and who was among them?

I think we should be 14. Now I'm recalling from the number of us taken out in two Peugeot 505 cars [station wagons] from the Jos motor park to Abuja. Six were in one vehicle while eight were in the other, making 14. I don't know whether you want me to recount the names so as to make the number?

You can mention some of them.

Okay. Lieutenant-Commander Bola Soetan, staff officer [finance] to General Diya, who was accused of stealing but he was discharged and acquitted. Hajia Halima Bawa, who was also accused of stealing along with him - that's another story entirely. Then the four bodyguards who were said to have marched to the house of chief of army staff: Abimbola Owatimehin, Ibrahim Kotangora; DSP Bawa, accused of receiving stolen goods and of aiding and abetting and whatever, one corporal who was serving the wife of General Tajudeen Olanrewaju. I can't remember his name now ... and, of course, the Abacharist man, what do you call him ... emmm ... ehen en... Yomi Tokoya who was really mad about the injustice of keeping us for so long after we had been discharged and acquitted.

After you had been discharged and acquitted, as you rightly said, and you were still being held in prison, did they relax the sanctions on you? Were you allowed more freedom than before?

After you had been discharged and acquitted, as you rightly said, and you were still being held in prison, did they relax the sanctions on you? Were you allowed more freedom than before?

Essentially no. Those discharged and acquitted were still held in handcuffs and leg irons. Any relaxation you got at all was either on individual basis or on the discretion of the people guarding you. Both the discharged and acquitted and the convicted were still held in the same wards and rooms, as we were before the judgment, in wards C, D, J and a fourth one. In my own cell, to my right was Colonel Bako who was convicted - actually all the detainees surrounding me in Ward C were those convicted. They were with me from April 28 to about June 8 when they were eventually taken away with [General] Diya. So, I was in the company of those people who were convicted - Engineer Adebanjo was in Cell 2, Niran Malaolu (your fellow journalist) was in Cell 3, Colonel Bako was in Cell 4 and I was in Cell 5. Upstairs, we had Major-General Olanrewaju, Major Mohammed, DSP Adebowale and Ibrahim Kotangora.

We have heard a lot about your experience in prison but we shall come back to that later. Meanwhile can you recount the day of your arrest? How did it happen?

Oh yes it was a fateful day in the sense that I had got my family together to travel for Christmas. Already I had applied for leave to last from Monday, December 22 till January 5. I had borrowed a pick-up van from a friend to carry yams, rice and other items to my hometown for the Christmas celebration. It was expected to be a special one for me and my family because barely a week before the proposed commencement of my leave, we (the CGS [i.e., General Oladipo Diya's] entourage) had just escaped what looked like an assassination attempt through a bomb blast at the Abuja airport. My family was looking forward to having a thanksgiving dinner for friends and well-wishers on December 25. Thus everybody had packed and was ready to leave Abuja for Ilesa the following day. At about 3.30 a.m., I was feeling tired and decided to have a nap and wake up at 6.30 a.m. or thereabouts ... It couldn't have been more than forty minutes after I decided to sleep when my wife tapped me and shouted, "Femi, Femi, Femi, what's that noise about?" So, I got up and looked through the window and saw people with guns. They were not in army uniforms, rather they were in jeans and T-Shirts and fez caps with machine guns. I was thrown into a panicky situation because I didn't know what to do. I was hearing heavy footsteps and the whole place was soon turned into a bedlam. And here I was in a khaftan-like night dress without underpants! I started looking for something to wear but meanwhile it was like I didn't know exactly what to do. I was just walking up and down and I was hearing noises. Soon I was telling my wife, "Go to the bathroom, go inside the bathroom." Before I could even finish telling her that, I just heard this heavy bang on the door and the cocking of guns with the warning: "If I count three and you don't open, I'll shoot!" I said, "Wait, I'm coming, I'm opening the door." By this time I had been able to lay my hands on something, this boxer short [pants] to wear. The next thing I heard was wham! I was slapped with the side of the machine gun. I was almost unconscious. I started asking: "Why? Why? Why are you beating me?" The next thing I received was another blow to my face. By the time I was led to the sitting room, my children had been lined up like a reception committee (for me). By that time, I had a cut on my lips and another on my head. I was bleeding like a punch-drunk boxer. On my way downstairs, I saw somebody in handcuffs who later turned out to be the ADC to General Diya. Apparently, if I may rewind the tape (of events) for you, as I gathered seven months later, it was the ADC, Major Kayode Keshinro who was picked up from his house and asked to lead the team to my house. As I later learnt, he was picked up almost in a similar circumstance but he was allowed to dress up and was not beaten like me. I need to stress this point because mine was a special treatment. they kicked me, slapped me, shoved and pushed me like a criminal. I suddenly regressed into childhood because I had never received that kind of beating in my life before. Somebody just comes into your house, he is not telling you that you are under arrest, not informing you about any crime committed, just started beating you up and banging your head with machine gun. I was literally thrown down the staircase in front of my children. I can remember one of my children telling me after my release: "Daddy, I know you to be a strong man. I have never seen fear in your eyes in my life. But that day I saw fear in your eyes." It's as bad as that. My children saw their father being battered and there was nothing they could do. It was so uncivilised.

Where were you taken to?

When we got downstairs they continued pushing me; and neighbours who had been woken up, apparently by the commotion were watching the whole incident from their windows. I was not wearing any shoes, not even bathroom slippers that I normally wore. I was in this light khaftan-like house dress with virtually nothing under (except the boxer shorts) and this was harmattan [cold]period (in Abuja and the North). They put me and Major Keshinro in this station wagon and drove us away but I noticed that the team left about two of their men behind.

What, at the time, did you think could have been the motive for your arrest?

What I thought in my brain at the time was the bomb blast (at the Abuja airport) of the previous week and the press coverage which they did not want. I thought maybe I was being held responsible for the wide media interest in the matter because we had heard rumours that some people were worried about the press coverage of that bomb blast. I thought they came to get me because they believed I was responsible for it. So, they took me away. By the time we covered about half a kilometre, I was already shaking, not much as a result of the physical wounds but because of the cold harmattan weather. One of them suddenly burst out: "Why are you shaking?" Then, they stopped the car and said, "Now, we are going to give you a thorough beating until you cannot shake any more." Then, that Major [Keshinro] started begging them, asking them to stop beating me. I kept quiet but I was still shaking because there was nothing I could do but to shake. Somehow, they stopped and went back to the vehicle and sped so recklessly as [if ] they wanted to finish me in an accident. Finally, we reached our destination - Aso Rock. [Guards] opened the gate for them and when I got there, the whole place was like bedlam. I saw about 40 to 50 of these people dressed in jeans, canvas shoes, blue or black T-shirts, fez caps, windbreakers and some of them wearing masks (hoods). Later I gathered that these were the people called the Strike Force. Ironically, I had been working in the Aso Rock Villa for about four years but I did not know of the existence of this Presidential Strike Force. I saw Major [Hamza El-]Mustapha also. He was dressed in trousers, a light-colour shirt and had this walking stick which they can sit on at time[s]. He was sitting on it as I was pushed to him. He said, "Yes, you stupid Yoruba man. So, where is Diya now? Where is Olanrewaju now? Where is Adisa now?" Anytime he asked this question I just opened my mouth like this (in astonishment). I was wondering what else could have happened because all along I had thought that I was being arrested for this press coverage thing and that after this beating and interrogation they would release me but until he was asking: "Where is Diya now?" "Where is Adisa, you this stupid Yoruba man." I didn't really know what was happening. At times he would ask again, "You stupid professor, yes, we have seen your speech, that draft speech you wrote ... And you want to be Foreign (Affairs) Minister, you want to take [Chief Anthony] Ikimi's job, no bi so[isn't that the case]? You go share one [pair of] trousers with Ikimi." So anytime he said something I would just exclaim "ah!" And anytime I said "ah!" like that I received a blow, gboam on my head from one of those fierce looking boys. One would give a blow from the right and as my head turned left another one would send it back with another equally deadly blow. In other words they were tossing my head around like football.

Was this happening in an open field or in a room?

In front of the office of the head of state, in the courtyard. That's where the action, if you will call it that, was. And like I recorded it in my initial statement two weeks later, I said they were beating me like an offending goat on a village market day. That describes what I felt. You know the village system? On market days any goat that eats anybody's yam or any foodstuff would be beaten from stall to stall. Then the man [Major El-Mustapha] said, "No, well, stop beating him. We are supposed to be disciplined people." Then he turned to me, "Go and kneel down there." Meanwhile I saw Major Keshinro also being beaten but I was the star attraction. I saw DSP Adebowale too. Everybody was kneeling down. Major Fadipe was in another corner. He had been so badly beaten that he was bleeding profusely from the head. Now, I must remember this. Anytime Mustapha was talking to me somebody would just come and give me a blow on the back saying, "CSO [Chief Security Officer] is talking to you and you are standing, kneel down!" Another one would come and say, "CSO is talking to you and you are kneeling down, stand up!" and he too would give me a blow. Somebody told me later that he thought they were going to kick me to death the way they were raining blows on me with both hands and feet. There was a time when somebody took a very vicious kick at me like a football on the penalty spot and I literally flew over the bar. Major Fadipe later told me, when we had time to discuss, that I was, indeed kicked about three feet above the ground. After some time one small boy came to challenge me that he saw me one day talking to a white man at Sheraton Hotel, Abuja, and demanded what I was telling the man. Before I could answer he was already all over me saying, "You were passing information, you were making arrangement for the coup." And I was saying, "ah, ah, no, no. I normally go to Sheraton, I go to NICON-NOGA [Hilton Hotel] either on official duty or to play tennis or for official function." He said, "No." each time during the interrogation or shall I call it during the accusation, I would get an occasional blow here and another one there. Suddenly Mustapha ordered some of the boys to pour ice cold water on me, and this was around 5.30 a.m. during the harmattan. So, they started pouring ice water on my body. And now, this may shock you. The son of General Abacha, Mohammed was the one applying electric torture prod on me. I have about six witnesses to bear me out on this. He would place the electric prod on my wet body - you need to experience it to know what I'm talking about. It is exactly like the electric shock one receives by handling a faulty electrical appliance with wet hands. I could not understand why I was so specially tortured by Mustapha, Mohammed and their boys. Mustapha's own was more psychological than physical. He would say, "You stupid Yoruba people, you think you are smart. See now, who is more knowledgeable - you a professor or me? Who is down now? Who is up?" He said, "You people think you are wise.

You are knowledgeable abi[not so]? Stupid professor. I never trusted you, you see, your antecedents don't even make me trust you. You are a traitor to your own cause. By coming to work here, you are already a traitor to your own cause." I don't know what he meant by my antecedents that made him not to trust me. But he reminded me that in 1994, he seized my ID card because he didn't want me to work in the villa. So, this idea that some people own the villa and they are the people who could work there and that even when somebody like Diya is working there and he wants to employ his own people you must be the one to decide who is good for him and who is not. This is, from my own interpretation, what I could read from this kind of attitude; and if you care this is my own analysis of the Nigerian situation to day because otherwise at that point in time, I could not understand why my ID card was seized from me but later on I came to understand it. They said they knew me from ABU [Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria] as 'radical'. I am somebody who does not agree with the second class citizen position. I have never accepted it. I have always fought it and I have always done so successfully. SO, they saw me as somebody who is not the submissive type. Even the ADC [military body guard] to the head of state [General Sani Abacha], Major Abdallah, was in the same league with the Mustaphas. He saw me and said, "Professor, even you. We gave you a small opportunity to come and eat and better your life a little bit and see what you have done." Later Mustapha threatened that I should tell him what he wanted to know and that if I didn't, he pitied my family. I didn't understand what he meant at that point in time but I later got to know. We shall get to that later. But before finishing with me, he ordered that his boys should go back to my house and pack all my documents, files, books - anything they could lay their hands on. He said, "Pack everything here and if he likes, he can go to the human rights commission in, ... Professor, where do you have your human rights commission. The Hague? (He did not know that it is in Geneva). Let him go and report there." All the time I was asking myself: Why are they treating me like this/ I am not a soldier yet my own physical harassment was more than even the soldiers' because I can now even remember something else they did to me when they were taking me from my house to Aso Rock. I had just discovered that my (neck) chain had cut when one of them saw it and demanded what it was. He then ordered one of the boys to throw the chain in my mouth and allow me to choke on it. So, I don't know what Major El-Mustapha must have told those boys but the only thing he told me was that I wrote a draft speech and I was to be made minister of foreign affairs. Those came to me as a shock because I didn't know anything about it at all. Then they took me from Aso Rock to Gado Nasko [Barracks] guardroom. The people who took me there were very abusive while en route there. They said, "Let's shoot his leg." "Let's gouge out his eyes." - all sorts of things. As I have already told you, I was badly, badly shaken. I was like a chicken soaked in water. Remember it was harmattan period. At Gado Nasko Barracks, they took down the names of new arrivals and soon allocated rooms [cells] to us. When it was my turn they asked for my name and I said I am Professor Femi Odekunle. Thereafter I did not experience any further beating but other people were beaten in terms of bulala [horse whip]. There were eight guard rooms [cells] in all. I was allocated to Room 4 where I met Colonel Shoda, Colonel Chiefe and two other people, meaning that we were five to a room. You were not allowed to go to the toilet until they were ready which was twice a day, at most. The daily routine at Gado Nasko is like this - in the morning around 7 a.m. or 8 a.m. they would open one room at a time and tell you to go to the toilet. The other rooms remain locked while all of you in the opened room are marched to the toilet though you were not supposed to look to your left where the other detainees were so that you wouldn't know who was there. when you get to the toilet, there is a guard waiting and watching you while you're doing 'No.1' and 'No. 2'. I hope you understand that - No. 1 is urinating while No 2 is shitting [defecating[. Sometimes as you are about to embark on either No. 1 or No.2 the man would shout, "Time up!" and that's it. You've lost your chance. It is not a question of going there to spend five or 10 minutes. For the first two weeks, we did not brush our mouths; and for the first one and a half weeks, no bath. When it was exactly one and a half weeks we were taken out to have our bath. I quickly removed my clothes, no shyness or any inhibition of any sort, and took the opportunity to wash my already dirty clothes because we were sleeping on bare cement floor. While I was having my bath, I could remember Major Ishiaku saying, "Oh, Prof., I didn't know you are light skinned, I thought you're black." That's to show you how dirty I really looked. And that was the first time, when I looked at the mirror, I saw my left eye looking like the multi-colour picture of the earth that you take when you are coming from outer space, with green, blue, brown patches all over. that was how my left eye looked and I thought I was in real trouble. Actually, I thought I had got brain damage because one and a half weeks later, I developed vertigo, a dizzy spell whereby when you stand up you feel like falling down. It could be on the right or on the left. One day, we were all marched out in handcuffs to go and see a doctor. It was the first time since my arrival in Gado Nasko that I would be handcuffed. Before then, I was not, may be others were. Again, you could not see the military doctor privately. A guard had to be around. I told the doctor that I thought that I had brain damage but he said he didn't think so. Up till now, I'm not convinced until I have had the chance to seek proper medical examination of my head, because I received too much battering on the head, especially on the left side. Those boys really had homicidal intentions in their dealings with me.

You are knowledgeable abi[not so]? Stupid professor. I never trusted you, you see, your antecedents don't even make me trust you. You are a traitor to your own cause. By coming to work here, you are already a traitor to your own cause." I don't know what he meant by my antecedents that made him not to trust me. But he reminded me that in 1994, he seized my ID card because he didn't want me to work in the villa. So, this idea that some people own the villa and they are the people who could work there and that even when somebody like Diya is working there and he wants to employ his own people you must be the one to decide who is good for him and who is not. This is, from my own interpretation, what I could read from this kind of attitude; and if you care this is my own analysis of the Nigerian situation to day because otherwise at that point in time, I could not understand why my ID card was seized from me but later on I came to understand it. They said they knew me from ABU [Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria] as 'radical'. I am somebody who does not agree with the second class citizen position. I have never accepted it. I have always fought it and I have always done so successfully. SO, they saw me as somebody who is not the submissive type. Even the ADC [military body guard] to the head of state [General Sani Abacha], Major Abdallah, was in the same league with the Mustaphas. He saw me and said, "Professor, even you. We gave you a small opportunity to come and eat and better your life a little bit and see what you have done." Later Mustapha threatened that I should tell him what he wanted to know and that if I didn't, he pitied my family. I didn't understand what he meant at that point in time but I later got to know. We shall get to that later. But before finishing with me, he ordered that his boys should go back to my house and pack all my documents, files, books - anything they could lay their hands on. He said, "Pack everything here and if he likes, he can go to the human rights commission in, ... Professor, where do you have your human rights commission. The Hague? (He did not know that it is in Geneva). Let him go and report there." All the time I was asking myself: Why are they treating me like this/ I am not a soldier yet my own physical harassment was more than even the soldiers' because I can now even remember something else they did to me when they were taking me from my house to Aso Rock. I had just discovered that my (neck) chain had cut when one of them saw it and demanded what it was. He then ordered one of the boys to throw the chain in my mouth and allow me to choke on it. So, I don't know what Major El-Mustapha must have told those boys but the only thing he told me was that I wrote a draft speech and I was to be made minister of foreign affairs. Those came to me as a shock because I didn't know anything about it at all. Then they took me from Aso Rock to Gado Nasko [Barracks] guardroom. The people who took me there were very abusive while en route there. They said, "Let's shoot his leg." "Let's gouge out his eyes." - all sorts of things. As I have already told you, I was badly, badly shaken. I was like a chicken soaked in water. Remember it was harmattan period. At Gado Nasko Barracks, they took down the names of new arrivals and soon allocated rooms [cells] to us. When it was my turn they asked for my name and I said I am Professor Femi Odekunle. Thereafter I did not experience any further beating but other people were beaten in terms of bulala [horse whip]. There were eight guard rooms [cells] in all. I was allocated to Room 4 where I met Colonel Shoda, Colonel Chiefe and two other people, meaning that we were five to a room. You were not allowed to go to the toilet until they were ready which was twice a day, at most. The daily routine at Gado Nasko is like this - in the morning around 7 a.m. or 8 a.m. they would open one room at a time and tell you to go to the toilet. The other rooms remain locked while all of you in the opened room are marched to the toilet though you were not supposed to look to your left where the other detainees were so that you wouldn't know who was there. when you get to the toilet, there is a guard waiting and watching you while you're doing 'No.1' and 'No. 2'. I hope you understand that - No. 1 is urinating while No 2 is shitting [defecating[. Sometimes as you are about to embark on either No. 1 or No.2 the man would shout, "Time up!" and that's it. You've lost your chance. It is not a question of going there to spend five or 10 minutes. For the first two weeks, we did not brush our mouths; and for the first one and a half weeks, no bath. When it was exactly one and a half weeks we were taken out to have our bath. I quickly removed my clothes, no shyness or any inhibition of any sort, and took the opportunity to wash my already dirty clothes because we were sleeping on bare cement floor. While I was having my bath, I could remember Major Ishiaku saying, "Oh, Prof., I didn't know you are light skinned, I thought you're black." That's to show you how dirty I really looked. And that was the first time, when I looked at the mirror, I saw my left eye looking like the multi-colour picture of the earth that you take when you are coming from outer space, with green, blue, brown patches all over. that was how my left eye looked and I thought I was in real trouble. Actually, I thought I had got brain damage because one and a half weeks later, I developed vertigo, a dizzy spell whereby when you stand up you feel like falling down. It could be on the right or on the left. One day, we were all marched out in handcuffs to go and see a doctor. It was the first time since my arrival in Gado Nasko that I would be handcuffed. Before then, I was not, may be others were. Again, you could not see the military doctor privately. A guard had to be around. I told the doctor that I thought that I had brain damage but he said he didn't think so. Up till now, I'm not convinced until I have had the chance to seek proper medical examination of my head, because I received too much battering on the head, especially on the left side. Those boys really had homicidal intentions in their dealings with me.

Did you get details of the arrest of General Diya and others later?

Yes, but that was in the prison because despite the tight security situation, we found a way of talking to one another, particularly at the beginning and towards the end, not during the investigations or during the trial. SO, you get to exchange views in a very secretive manner because you are not allowed to engage in open discussion. take Gado Nasko Barracks, for example, we were three in a room, definitely we would talk. For example, it was there I asked Keshinro why he brought the arresting squad to my house. Major Ishiaku and I also talked but I didn't know that both Adisa and Olanrewaju were there until weeks later when we got to Jos.

What about General Diya?

General Diya, I understand, was in a guest house somewhere in Abuja where he was detained.

But you must have met at the Special Investigation Board (SIB).

Not really. But before we go to the SIB stage, let me say more about the experience in Gado Nasko guardroom. The summary of it is that you are inside 24 hour a day and you are only allowed to come out for two things. One, to go to the toilet in the morning, in military fashion or, let me say, in an unnatural fashion. You are marched out and must not look to your left, neither must you talk to anybody and somebody is at door shouting, "Time up!" even before you do anything. One evening, after staying for about two weeks, they called me: and anytime they wanted to call anybody we were always afraid. There was the case of one Hausa boy whom they brought, for the time he spent with us he did not stop saying "Laila ilalahu, laila ilalahu." [There is no other god but Allah]. he was panic stricken and he was shaking all the time. He was totally distraught. He was almost psychiatric. For when they opened the door, while he was still shouting laila ilalahu, they gave him more thorough beating. Thus, anytime they called you, you were bound t be afraid. We even heard that those in the general store area, who were more than 20, were regularly flogged. In other words, as bad as our own case was, we had, I hate to use the word, a better status treatment compared to those in the general guardroom.

Who were those?

Corporals, sergeants and others like the Cokers, the Owatimehins and the Kotangoras. Those people suffered more. They would just come and say, "Oh, yes, we have to cane you now." And wham, fiam, wham, wham, fiam, the bulala[horse whip]would be sounding on their bodies. They would, at times, beat them before breakfast. They would say, "Do you want your 'hot tea' before or after food?" The 'hot tea' is either six or 12 strokes of the cane. There was a day one of those flogging detainees saw one detainee and said, "Your body is too smooth, it needs some patterns" and he caned and caned and caned him until he collapsed only to cover himself with a towel, the only "dress" on him when he was arrested. One day, when it was already two weeks, they woke me up in the midnight and they said, "Professor, you are wanted". When I got there, I saw this major whom I later learnt to be Major [Adamu] Argungu, a military police attached to the [Aso Rock] villa. He said, "Professor, do you know me?" I told him I didn't know him. He said, "Well, how do we get the key to your office?" I told him he could always collect it from the registry. After threatening that he would deal ruthlessly with me if he found any drawer or cabinet locked, he then turned to the guards and asked why I was not in chains. One of the lieutenants told him that it was because there were not enough chains. Then Major Argungu said, "But that's standard procedure. Go and bring one in my car." So they went for it and chained me there and then. So I joined the group of chained detainees. One day again, this [strange]man came to wake me up and said, "Professor, you are wanted." I met Major Argungu, I was in handcuff and leg-iron; and he asked me to enter his car. I did. At the back was a bouncer, I mean somebody who looked like a bouncer. He said the CSO wanted to see me. When we arrived in the villa, they took me to the basement and I was just looking because this was a situation in which somebody could just pick you and kill you, just like that. I was the only one in the basement. have they brought me here to be slaughtered? I asked myself. Later, the man came in, that's Major Mustapha. he said, "Bring him up." They took me up to him and he said, "Sit down." I, who had not seen any soft surface for two weeks? He said, "Professor, I want to help you but you have to tell me all you know about this matter. We take it for granted that military people can do things and the civilians may not know when they are participating but we will make it a military affair. We don't want any civilians so, just tell me what you know and we would help you." I said I just wanted to see my family. he said, "I will help you but first tell us what you know. We have talked to Diya, he has talked a lot and has mentioned your name. We have talked to Patrick Aziza and he too has mentioned your name. So, definitely you must have something to say about ..." Sorry, I have omitted something and it is very vital. When that Major Argungu called for me and asked for the key to my office, three or four days later he was at my office and when I was picked up to see the CSO, he said, "Professor, so you write useless memos. I saw the letter you wrote to General [Jeremiah] Useni [minister in charge of the federal capital territory, FCT]. Is that the job of a professor? Writing about [Chief Obafemi] Awolowo not getting a befitting road in Abuja. You are a useless professor. Is that what you are supposed to use your brain to be writing?" So, I was trying to say that there was nothing wrong in raising this kind of issue. He said, "are you arguing with me?" I said no. The thing is that I had written a letter as far back as 1994 when I was still in ABU on my personal letter head which bore my name - Femi Odekunle, Professor of Criminology - a very polite letter indeed that requested for amendment over this complaint in Abuja that all nationalist leaders had double carriage roads, large or long streets [named after them] except Chief Awolowo. I did not believe until I got to Abuja to see that it was true and that it was only Awolowo who had something like an alley named after him. I pleaded to Useni that it might not be his fault, may be an oversight or something on the part of the previous administration. I wrote that he did not need to set up a committee to do this, he needed just to do it and it would be to his credit. It was the copy of that letter that was found in my possession and for which the major was insulting me and rebuking me for being a professor who is expressing ethnic sentiments. I told him it was not ethnic sentiment. he was not done with me yet. he accused me again of being Diya's favourite. He said, "Why is it that anytime you people are going in a convoy the CGS would ask you to leave your car and sit with him in his own car? So, you are his favourite no be so [isn't that so]? You must have been enjoying it, but now you're paying for it." He said all kinds of things portraying the fact that he was a prejudiced major. It also shows that they had no reason for arresting me in the first place. It was only after I had been arrested that they were looking for an offence to hang on my neck. But why this prejudice? Was it because of where I come from or was it just an attempt to clear everybody of my kind? Sorry for the digression. We can now connect with the Major El-Mustapha interrogation. He was saying that he would help me if I could tell him where Diya had sent me but I told him that I didn't know anything but he said they had talked about me, Diya and Aziza. I said, "Well, let them come and face me because I do not know anything about what you are telling me." After about 30 minutes or so, I said: "In the name of God, I beg you to leave me alone and let me go back to my family." He said he was only ready to help me if I could help him. I thought to myself that this man wanted me to help him by incriminating myself. I said even though my life depends on this matter there was no way I was going to lie against myself or against anybody. It was a no-win situation for him. After about thirty minutes, he ordered that I should be taken out and carried back to the guardroom. two hours after getting back I was again woken up and asked to come out only to see black Marias outside and people being moved out. now, I was seeing people I had never seen before like Commander Soetan, I never knew he was detained in Gado Nasko with me. The way we were transported out in the black Maria was horrible and I will use my own experience to illustrate the inhumanity in the transportation. They chained my right leg to the left leg of the person sitting next to me. Then they chained the left leg to the right leg of the other person sitting to my left. In the same fashion, my two hands were handcuffed to those of the same people. I was in this position throughout the journey from Abuja to Jos, a journey which took 12 hours to accomplish instead of the normal four hours. I don't know whether this was deliberate to punish us the more. They never stopped to allow us to eat or go to the toilet. It was horrible. In my own black Maria, we were only three chained together like 18th century slaves and locked up from outside. If there was a fire or an accident, we would have perished before the keys could be procured. when we were off-loaded in Jos, the three of us had to move like that over pavements, staircases and along narrow paths. It's better seen than imagined. Later, we were received by Major Mumuni and separated before being distributed to different cells. The room where I was put had evidence of fresh cement. They had dug hole in the ground and implanted iron hook into a concrete base. I was chained to the hook despite the fact that it was a solitary cell - meaning that I had to stay and sleep on the same spot. We were not given the luxury of moving up and down - meaning that we were not only detained in one room but on one spot. Thus, Gado Nasko [cell] looked to me like NICON-NOGA Hilton Hotel when compared with this creation of man's ingenuous cruelty. In my own case, I'd say I had a raw deal. My leg-iron was removed and instead, I was handcuffed to the iron hook. You can imagine the sorry picture of me tied down like an Ileya [Id-el-Kabir] ram waiting to be slaughtered as it were.

So, when did you learn that your arrest had to do with the alleged coup plot?

As I had said earlier on, my belief was that I had probably been arrested over the press coverage of the [December 13, 1997] Abuja airport bomb blast and when I got to the villa and Mustapha started questioning me, "Where is Diya now? where is Adisa now?" and so on. It was the accusation that I wrote the draft speech that I wanted to be foreign [affairs] minister that gave me a hint of what they were up to. My brain told me that this might be an attempt to get rid of those they didn't want near the corridor of power.

Now, tell us about your first night in Jos.

The way I was 'tied' down was quite painful. throughout the night, I was moaning and sort of literally crying out for help ... There were eight people guarding us at each given time and they belong to the Presidential Strike Force (2), the Military Police, SSS, Mobile Police, Ints (Army Intelligence Officers), DMI and the Prison. There is always a team leader for each ward. So, in the morning when one of the guards opened the door, I drew his attention to my horrible situation saying the way I was I might soon die. He went back, I think to hold consultation and seek permission, and came to release one of my hands from the hook. Thus, I could at least stand up and stretch the free hand while the other remained hooked to the floor. In this situation, I was eager to get over my case, if any. So, I was always asking, "When am I going to see the SIB?" Then one Tuesday, they just came and said, "Come out, let's go to the SIB. No be yu say yu wan talk[After all, it is you who have been pressing for an interview with the SIB]?" The way they put it, it was as if I was ready to spill the beans. I said, "No, I was just trying to ask when it would be my turn so that I could get over this uncertainty." Well, that was the first time that I went before the panel.

That was the Chris Garuba Panel?

So I thought but the first panel I was taken to was a preliminary one headed by Lieutenant-Colonel [Anthony] Omenka. He was lord and master of the panel. It was a devastating experience. First, when they take you, they take you to Rayfield where the Preliminary Investigations Panel, PIP, was. Just like our prison yard was guarded with armoured vehicles, that place was also guarded and you are in chains. They ordered everybody to sit down outside on the ground, sometimes under some trees and at times inside some garages where iron hooks had also been implanted, just like in the prison cells. About three or four of us were put in a garage but it is only you are many that you are given the luxury of being chained in the ground inside the garage. If not, you are all kept in the open field and separated from one another so that you cannot discuss with the person nearest to you. Oftentimes, the cold harmattan wind will be biting you and you may be in this position for 10 hours before they call you in and by the time they do this, the elements must have beaten the hell out of you.

In your own case, were you still in that scanty house dress you were wearing when you were seized [arrested]?

Of course. And I almost froze to death but later they issued us military blankets and sweaters which I later started to wear over my khaftan night dress. The effect of the harmattan was horrible. My lips were cracking, my ankle and back heel were lacerated and were as hard as yangi [laterite] because, all along I was bare footed. The Mustapha boys did not allow me to wear even slippers when they came to seize [arrest] me. But I devised a means of alleviating the effect of the cold harmattan on my feet. Anytime we were supplied eba or any other food item in cellophane bag, I made sure I retained the bag, which I later used to wrap round my naked feet. And, of course, I used the cellophane bags for other purposes which I don't want to tell you.

(Cuts in) For doing No. 1 and No 2?

You are right [laughs]. remember I told you that we had restrictions on when to go to the toilet but man must just survive by any means. Back to the PIP story. When we were finally called to enter the room, immediately you reach the pavement, they would remove the chains on your legs and the handcuffs. Finally I got in after so many hours in the open, that was around 6.p.m. The head of the panel [Omenka] said, "Ehnn, Professor, I used to know you in the 80s when you used to come from ABU to deliver lectures and there was an occasion you delivered a lecture on security and development, I think that was around 1989. I knew you at that time and I respected you but now look at you, you are like a wreck ... Now, tell us all you know about why you are here." I said, "But I don't know why I am here." He cut in. "Don't tell me that, don't tell me you don't know why you are here. You mean you want to tell me as educated as you are, that you don't know why you are here?" I told him all I knew was that they said I wrote a speech and that I wanted to be foreign [affairs] minister and that I was sent on some errands. Then he started insulting me. In the end, he said, "Anyway, you may not know what you were doing because you are a civilian, so go and write everything down and we will use you as a state witness." I said, "Goodness!" Can you see the offer there? They wanted me to incriminate myself. Well, I went to the statement room and, despite the damage to my head, my thinking faculty was still intact but you have to be careful what you are doing because you are already tired and exhausted. I had been out for more than six hours and I was in front of this man for one hour during which I was scandalised and verbally abused only to be confronted by another man saying, "Oya [now], write your statement." But I wrote the statement all the same. I had no choice but to state exactly what I had told the panel that I knew nothing about anything at all. I made one categorical statement that though my life was at stake, I was not ready to tell lies against myself or anybody for that matter. I also said that even if they perceived me wrongly, I was even ready to take the blame for being so perceived or be punished. They could do anything but they should not rope me into what I did not know anything about. That was the meat of the statement I made and I had to do it three times after each interrogation by the Omenka panel.

Was there any time he expanded his offer that you should become a state witness?

No. But a week later, they brought me to the panel again for another round of interrogation. But the discussion appeared more respectable. It centred on my discipline, my philosophy, how I was employed, my relationship with General Diya, my job specification and so on. I told them I was the chairman of the Advisory Committee to the CGS on socio-Political and economic matters. After the discussion, I was again asked to go and write a statement. I did.

How many officers interrogated you?

They were between eight and 10.

All of them firing questions at you?

Ehnn ... No, 95 per cent of the questions and the dialogue was done by Omenka. he was, like I told you, lord and master of the interrogation team. The others just say one or two things which are of no consequence. He was the alpha and the omega, the decider of what happens to you. On January 15, in the afternoon, I was picked for the third time again for the PIP. When I got there, I was outside till 12 midnight before I was called in. I was totally exhausted, famished and gaunt. The man started as usual. "Professor ..." Before he could begin I just remembered what he said to me during the first interrogation. He had said, "Professor, I'm going to shoot you. I'm going to eliminate you. I'm going to waste you." I remembered and shivered. He added, "Professor, you may say you are a good person. Have you read a book called 'Why Bad Things Happen to Good People'?" I said I had not. He said, "Well the man who wrote it is dead. when I finish with you, you'll meet him in the [Great] Beyond and discuss the book with him." I said, "My God!" So, during this third interrogation: the man started, "Professor, you said we would not find anything in your house if we go there. What about this?" Indeed, it was my handwriting. Then he read a portion out. He took another and read another portion out of context. Some of the documents were written while I was in ABU, others [were] written in 1994. Those of 1994 were in my official capacity as chairman of the Advisory Committee to the CGS. It appeared they were just trying all means to deflate my lifejacket and get me drowned in the alleged coup plot. I blurted out: "No, no, this is not fair. how can you take a document of 1994 and say it has to do with what you say has happened/" The man said, "No, you are going before the tribunal." and passed the file over to somebody. Again I was asked to go and write a statement which I did at about 3 a.m. I must have apparently delayed the movement of the convoy back to prison. After I came out, we were all put in the black Marias, locked us up and left there till 7 a.m. when they came back and ordered us to come out and sit on the ground again to await further interrogations.

You mean you stayed there for 24 hours?

More than that. At about 7 p.m. I was again invited in but this time to appear before the Chris Garuba Special Investigation Board, SIB. The Omenka Panel was indeed a preliminary thing. The real panel was Garuba's. The question he asked me was why I had been militant in my write-ups about the C-in-C [Commander-in-Chief, Sani Abacha]. I explained to him that I was not militant, that that was [sic] they way we express ourselves in the university, and that we were often allowed to give different opinions including deviant ones on the same issue. After asking personal questions about myself and my family, Garuba signalled that I should be dismissed. I felt it was not fair to dismiss me like that and I wanted to say something by raising my finger but the provost marshall shouted me down saying I should go and argue my case in court. As far as he was concerned, it was a closed case against me, I happened to be the only one charged to the special military tribunal that day. All the others were told they had no case to answer.

How did the trial go?

On the day of trial [February 14], they came to pick us at about 12 noon. We were driven in a convoy and thoroughly guarded. I could not understand why they were treating us like very dangerous prisoners of war. when we got to Rukuba Barracks, they took us to the officers' mess. The whole place, as you might have seen on television, was guarded by these fierce looking young men with heavy weaponry. They formed something like a guard of honour for us to pass through before we could enter the black Maria. However, let me tell you that it was only the arraignment and judgment that took place in Rukuba Barracks. The trial proper was conducted at Rayfield. The dominant personnel in the security and handling of the alleged coup plot trial was the Strike Force. Ordinarily this is supposed to be a job for the military police and the military intelligence. The intelligence unit would gather intelligence and pass the same to the military police for the operational aspect. But in this case, to my own observation, the military police was marginalised. It was the Strike Force that dominated the whole affairs. You'll always see their machine guns at the ready. We were taken inside the games room of the officers' mess and Major Mumuni addressed us after which he distributed some files. Everybody had an envelope which contained the charge and a list of the prosecuting lawyers, their names, ranks and units, also the list of defence lawyers from which you can pick the one you want - all of them military lawyers. It also contained the legal instrument for covering the tribunal and the powers bestowed on it. when we were eventually marched into the courtroom, I was in the 'second row'. Inside the room there was the GOC of the 3rd Armoured Division;(3) there was [Brigadier-General] Ibrahim Sabo of the DMI [Division of Military Intelligence]; there was Lieutenant-Colonel Omenka walking around but the security officer in charge of making the place okay was Major Mumuni and there was a security officer in charge of operations from day one to the last. The court affair was a DMI show, supported by the Strike Force but you can easily see the link. Major El-Mustapha, who is in charge of the Strike Force, was also a DMI before he became the chief security officer to the C-in-C. Thus, you had the unholy trinity of Mustapha, Sabo and Omenka in charge of the court trial and security in Jos. The military police, which traditionally should be in charge, was relegated to the background.

Were you surprised when you saw the people in the court, the press men, the observers and the security personnel? What went through your mind?

It was like: "This is it!" By this time, I had made up my mind, sort of. Let everything hang out and see where it would land. The initial fear was no more there. I had now regained myself, my psyche, my self-confidence which I lost through the bitter beating I received during the first night. It was like I had no fear in me again and when I saw General [Victor] Malu [chairman of the tribunal] I was happy My initial assumption was that the man who would try us was General Garuba. Actually, I was expecting to see him as the judge. But I was happy to see General Malu, who I had known as a straightforward officer, who even once lost promotion because of his fairness and decorum. He has this reputation for being frank, calling a spade a spade and for doing what is right. I had this impression that he was not the type who could be manipulated to pervert justice. And he had just come back from ECOMOG as a hero, I was sure he would not want to tarnish that image. So, it's like this man is likely to do justice. When he delivered his opening remarks, it was like a ray of hope for me who had been in darkness since December when I was held - a flicker of light at the end of the tunnel. That was the impression I had. And I was praying to God that that flicker of light would not go out because he said he would not allow trial by ambush. It appeared he was determined to give everybody a fair trial, not the Patrick Aziza type. It was at this juncture that he asked us to talk and raise objection, if any, as to the constitution of the tribunal. It was here that General Diya made his famous speech. Others made their contributions and it was here that General Olanrewaju [and Adisa] expressed misgivings about military lawyers adequately representing their interest without fear. General Malu replied him very well. he said, "Well, you should have said this before now. You are in the system and you have never objected to this aspect of military law." This is a very important point and this is a point which people should emphasise. If these military people had taken enough interest in justice and fairness, the unfair procedures in terms of legal representation would have been expunged from the decree or from the system of military trial. My own belief is that ordinarily, as a civilian, I should have been tried in a civilian court because, I not being a military personnel, I should not be subjected to military law. Even if you are a military personnel, you still have certain rights and I think those rights include having lawyers of your own choice but Malu's reply, though I was affected, was right. He was saying in essence that the generals had been in the system all along and if they felt there was something wrong in the military legal system, they should have made their observations and recommendations known to the authorities, not when they were put on trial. So as it was, Malu had to apply the rules as they were.

How did you personally react to Diya's speech. Did it come as a bombshell? Were you alarmed or impressed?

I was impressed but I was not surprised because I had an inkling of what he might say or do at the trial. This is possible because anytime we were brought together I always tried to put myself at a vantage position where I could discuss with him. Remember that there was no real opportunity for us to interact. So, I had already known of what he was going to say before the day of arraignment. In fact, I would say I was surprised that he didn't say more than that. I can remember Malu saying that he should reserve his ammunition for the trial proper.

How about your own trial proper? Were you allowed to take the lawyer of your choice or compelled to employ one among the military lawyers? And what really happened during the proceedings? How long did the whole thing last?

Whenever we were taken to court, we were always happy because this was an opportunity for us to see the sky. Remember that we were always caged like wild animals in the zoo. It was also an opportunity to see other human beings, to move your legs, sit down on a chair, breathe in fresh, unadulterated air and sneak to say hello to somebody else. Before it came to my turn, five or six days after the arraignment, they started taking Diya and co for trial. I got to know this through Colonel Bako who was next door to me for four weeks without my knowing. The person who was there before was Colonel Chiefe but I thought he had been taken away. Anytime I was going to the toilet, I would only see the head of the person who appeared new but I could not recognise him because the rooms were dark. One day, I was able to see him when he was coming from the toilet and I was on my way there. I could not but exclaim, "So, Yakubu [Bako] you're the one?" He said, "Yes, I always wave to you, Prof., but you couldn't see me." Because he was charged with concealment [of treason] he was one of the first batch along with the generals to be tried first. So, it was Bako who whispered to me that Diya and others, including him [Bako], had been going for trial. The point is that we were still able to communicate despite the tight security. For four weeks, I was waiting to be tried because, up till the time, I was, perhaps the only detainee who had not been charged with any offence. I was thinking that maybe they had given up on me not to commit me to trial. But one Saturday [four weeks after the arraignment], I was told to prepare to go to the tribunal. And that was the first day I was meeting our lawyers. They worked as a group. they picked one for me, a military police, one Lieutenant-Colonel Badewole, who was not even around that day. While he was not around, two other lawyers talked to me. They were a lieutenant and a captain. These are sharp, brilliant lawyers who understood the geo-political implications of why I was there. One of the officers, I think, was a Northern minority who understood the North-South politics and how some people could be agents of the oligarchy and oppress and deal with anybody who they think would not accept the status quo. He understood the politics of the coup because we had discussions explaining the background and circumstances of why I think I was there. And he said from what I had told him, they had no case against me and that we would deal with it in court. I must say this; anytime I was briefing my lawyers, I was always on the verge of shedding tears because of the degree of suffering and inhumanity visited on my person by Mustapha and his boys. How on earth can we explain this, a professor of my own calibre and age who has served the country for so many years in different capacities being subjected to indignity and utmost brutality by some majors and privates who are nitwits ordinarily? I'm not being boastful. It's like you take a jewel and you start messing it up in the mud. You cannot explain it. Anytime I recalled the humiliation meted out to me by those nitwits I started weeping, not for myself, but for Nigeria, my country, which was being savagely reduced to nothingness. And I always asked myself, "Why were they doing this to me?" I saw myself as a victim of the agents of this tiny oligarchy who wanted everybody to kowtow and submit themselves as slaves; and anybody they didn't see behaving like that, they would find a way of dealing with him. It's not that I'm angry but I hate injustice. I hate unfairness and I have always fought this in my life. Nobody cheats me and gets away with it. I'd fight for my right but in this case, I was powerless and I could not fight for myself. here I was, a victim of prejudice. Not only that, I was a victim of a conspiracy. "Yes, we must get this professor whom we have known from ABU for so long, who does not accept a position as second class citizen." But I'll never accept it. I didn't accept it and I'll never accept it. They can hear this, why not? They know the kind of Yoruba they like. They know the kind of Igbo they like. Those who will not discuss injustice, who will only say don't mind them, that's the way they are; but when they are alone with fellow Southerners, they would be complaining. For me, it makes no difference even if you are my best friend. Among the Northerners, I have very good friends. I respect general Buhari very well, I respect Professor Ango Abdullahi very well. A lot of my friends and past students are from the North and I cherish my friendship with them but that does not mean we should not discuss geo-political issues that may divide us and which we may see differently because we are from different angles of these divisions. The principle of differential vulnerability says that we perceive problems differently - the way you are vulnerable to the federal character system in Nigeria is different from the way a minority is vulnerable to it. who benefits from it? Who loses from it? Differential vulnerability leads to differential solutions. I expect my lawyers to understand this factor in the political equation before their very eyes as it affects their client. Eventually, they were able to procure the charge against me from the secretariat and it was treason, later they added conspiracy to commit treason. The trial was thus anchored on this charge. On the day of trial, as they called my name, I excused myself to go to the toilet. You can call that anxiety urine. As I was about to go in, the guard detailed on me said, "No, the court is waiting, you cannot." So, I held it and walked back with my chains. The man refused because he had already received an order to bring me in. That's the soldier's mentality. Only death could counter that order he had been given except he received a superior order to counter it. So, when the trial started, my lawyer was at his best. He performed brilliantly by raising substantial and crucial objections to the admissibility of certain documents as exhibits, and he quoted some relevant laws to back up his submission. It was a crucial victory. My statement, four in all, were accepted as part of the proceedings; and when they were being read you could see pity on the faces of the panel. They were a recount of my arrest, the beatings, the false accusations by Mustapha and the threats of Lieutenant-Colonel Omenka to shoot, eliminate and waste me if I didn't say what they wanted to hear and how I said that though my life was at stake, I was not ready to tell lies against myself or anybody, for that matter.

Did you mention Mohammed Abacha as one of those who tortured you?

Hmmm... No. Because I had been warned that if I did that, I could be killed in prison. They would just come to your room at night wearing mask and do anything with you. So, I could not say that because at that point in time, they could come to my room and do anything to me. If you die in prison, Nigerians would just make noise, the international community would just make noise and I wasn't a politician. I am not someone who was known like Abiola or Yar'Adua. And even as Yar'Adua died in prison, Nigerians made noise and so what came out of it, let alone a university professor? So, it's like I'd been warned that there are certain things you do not say otherwise you'd pay dearly for it. SO, it was not in my statement. By the time they finished reading the fourth statement, my bladder was almost at the point of explosion. I signalled to my lawyer that I wanted to pee. He said, "Pee? Never!"

(Cuts in) Ehnn?!

It's not that he was being wicked. Rather, he said I could not interrupt the court's proceedings and more so the case was going on so well. So, why should this distraction come from the apparent winner? I was in a serious dilemma. My whatever [bladder?] had swollen yet I was soon to be called into the stand to be cross-examined maybe for an hour or two. I said, "Jesus!" How do I get out of this? I was feeling it. I was uncomfortable and I started blaming myself and cursing my bladder. So, I devised a means. I pretended as if I was about to vomit and at the same time raised my hand to the tribunal chairman. That one came to my rescue. He said, "Take him out, take him out." he showed very human and humane concern. You know, he has known me as a professor for many years, approximately. I had taught for about 24 years. Many people are my ex-students. [Senator] Iyorcha Ayu, for example, was my student. I have about two or three directors-general in the federal civil service who were my students. It's like I'm generally known in that part of the country. For example, even Lieutenant-Colonel Omenka had said he knew me as a professor in the 80s. So, when I went out to ease myself, the pee [urine] would not just come. I said, "Mo gbe" [I'm finished]. I don't know whether you've experienced this kind of thing before. when you delay too much before going to the toilet the bladder would swell so much that even the surroundings of your upper aperture would swell too and thereby making the urethra almost blocked because of the super-imposed load. Thus, urine will hardly come out not to talk of when you are supposed to do it in a hurry. Under my kind of situation, you need to relax before you could pee. SO, I had to rush back but the tribunal chairman insisted I must see a doctor. Remember, I had pretended to vomit. I eventually met a doctor who treated me for stomach pain. I went back to the tribunal but my lawyer was angry. "Prof., why now? And the case was going well for you. what happened?" I said he should not worry.

Sorry to cut in. Time is fast gone and we still have a lot of questions to answer. can you tell us a little bit about the judgment day?

Okay. Before we go to the judgment day let me briefly conclude the last question I was tackling. My lawyer asked that apart from the memo which I had written and which the prosecution was harping on, were there no positive memos at all from my office? Why should the prosecution take one out of hundreds of memos written over the years as an evidence that I was involved in the alleged coup plot? I even helped myself by shouting that the document being labelled anti-government was even positive. By the time I finished explaining the circumstances surrounding the writing of that memo, it was as if I had made my case. I talked for 30 minutes non-stop. When I finished, I said, "What have I got for all my contributions to the government? Chains!" I held up my hands to show the handcuff. I said, "This is all I have got for all my efforts to improve the lot of my country. I didn't mean to be emotional but the effect was not lost on the court. After this, we started waiting for the judgment day.

So, how long did the trial last?

Just between two and three hours. On April 30, we went back to court for the summary when the judge advocate was to summarise the whole trial; and from there, you can know how the judgment would go. My own summary was that the prosecution did not produce any witness, just a document which was not even admissible as exhibit. On judgment day, they came as usual with barbers to cut our hair and shave our heads to make us look presentable. They bought new jeans and shirts for those who needed new dresses. They were brand new second hand clothings, of course. we went in a convoy to the venue, this time, Rukuba Barracks, and I sat close to General Diya. I told him that in ally my dreams I never saw him killed, that he should rest assured that he would not be killed. That whatever the outcome of the judgment that day that would not be the end of the matter. I had also prepared my own allocutus because I thought after the verdict, as is customary, they would allow us to talk before sentence. I had planned to say I was not seeking mercy of General Abacha but justice because I did not commit any crime. I intended to use the opportunity to tell my wife and children that I was innocent and that the reason why they were trying me and had found me guilty was because I am a Yoruba man who refused to accept second class citizenship in his country. I told Diya all these and he said, "You mean you'll say all these?" I said yes. He said it was okay. So, when they called my name and they said, "Treason, not guilty," my mind told me they were going to get me on the second charge, I was holding my breath. SO, when they said, "Conspiracy to commit treason, not guilty" I said, "Ha a!" People thought I was collapsing or I was about to faint. No, no, no. It's like saying, "Oh, at last!!" But I felt for those who had been found guilty, particularly Diya. Unfortunately, they did not allow them to say anything. At the end, we were all taken back to prison. I thought it was because it was getting late that we were not released. SO, I was hoping to be released the following day, but that night I suspected some foul play because suddenly at night I started stooling. It was almost non-stop; and within two days, I became like a broomstick and for four days I did not urinate. I was dehydrated thus I insisted that I should be taken to the infirmary but I was not taken there and all the medicine in this world could not help me. They gave me Talazole, they gave me Flagyl, they gave me another kind of antibiotics, they did not work. They even gave me Kaolin, it did not work. Then I started praying to God that, "God, you who made sure I was released miraculously, please, if there was any foul play to make sure that I don't get out of this prison, please, God release me." After about four days, I started getting better but I couldn't believe what happened to me in those three to four days. It was like I was going to die. Surprisingly, those of us who had been discharged and acquitted by the tribunal were still being held and suddenly there was this rumour that they were waiting for the PRC to confirm the sentences. But I said, "I was not sentenced, what concerns PRC with me again?" I could not understand this. However, something of interest happened on June 3, a Wednesday. We had slept, it was between 10 p.m and 11 p.m. In fact they had opened my door before I woke up. Then I saw Major Mumuni and two others saying, "Pack, pack, pack." They said, "We don't like the services in this prison again, we are going to relocate." Of course, that sounds insane to me. We had been there for six months, the trial had just ended. why should I relocate? And if you want to relocate why at 11 p.m? Anyway, within 10 minutes, we were all out with our loads on our heads like refugees. Every detainee, including the generals, were brought out. One of the guards moved nearer to us and said we were going to the airport. Our own reading of the situation was that they were taking us to Abuja. It was like we were going to be released or they were going to take us to Abuja, address us, to forgive and forget. That was our hope. So, when we got out, we were made to find somewhere to sit. I went to sit near Diya. Later he and the other convicted people were packed into the big black Maria and those of us discharged and acquitted were packed in two other smaller black Marias. We were in this position up till 12.30 a.m. when suddenly they said we were not going again. So, we were returned to our various cells frustrated. The next day, everybody's blood pressure shot up when they took the measurement. Why this kind of frustration? As it turned out, it was not going to be the last attempt to take us out. Barely a week later, precisely on June 8, we had just finished eating, at about 3 p.m., I just heard some people moving. They were opening doors, then I was able to see through my hole Major Fadipe and Niran Malaolu, those were two of the other four people with me on my floor, others were Engineer Adebanjo who seemed not to be himself again and Colonel Bako who was also sick but not as serious as Adebanjo. Major Fadipe was escorted outside by the guards. Later, we discovered that some people had been taken away and these included some of the convicted people. Those of us discharged and acquitted were left behind and later brought together to stay on only one floor. It was here that I was relocated to Diya's former cell. They left some convicted people behind. These include Alhaji Maidabino who was convicted of receiving stolen goods, he was director of finance, State House. Then Demola Ojeniyi, a driver convicted for stealing; Colonel Bako who was in the infirmary because he was vomiting and stooling at the same time, and the fourth person, Galadima. I think he is a private or corporal who was also accused of stealing, he is the son of the batman to the C-in-C. These four were left with us who were discharged and acquitted. All those convicted for treason, conspiracy or concealment were taken away, including Engineer Adebanjo, who was yanked off his sick bed.

You mean all those sentenced to death were taken away?

Yes, all of them. After this incident, we started our own waiting game. When were they going to release us? There were all sorts of rumours. By this time, we had heard that a new head of state had been sworn in after Abacha had suddenly died.

We want to confirm from you whether those taken out on that June 8 were actually kidnapped or was it a normal movement?

We understand that the GOC (in Jos) said he did not know anything about it. I say we understand because I am not in the position to say yes or no but in prison there is a way information flows and remember that some of our fellow detainees are military personnel too and they know how to get information from the military guards. For example, it was one of the guards who, on June 8, informed one of the detainees through the window that the C-in-C had died. I was told that he just peeped in and asked the detainee to come closer and whispered to him, "Abacha ya mutu." and demonstrated by simulating the slaughtering of a ram with his palm flashing past the neck fiam like that [demonstrates]. So, they said that on the first day [June 3], the intention was to take those people to where they would be executed immediately the PRC confirmed the sentences and that a bomb was to be put on the other plane conveying those of us who had been discharged and acquitted. That was the speculation. It was like there was no way they would let us go because they would not want all what we are saying now to be out and that's why they didn't want the discharged and acquitted to be released, particularly somebody like me.

Let's be a little bit analytical now. In your own assessment what do you think will be the future implication of all these things that have happened to the Nigerian military, a situation in which the chief of army staff, the chief of general staff and their commander-in-chief were trading accusations and counter-accusations over an alleged coup plot on video and in newspapers?

(Pause) We have here a juxtaposition of power-play in the military and in the ethnic complexities of the country. That's my own assessment and this man [Abacha] was a phenomenon. The way he wanted to succeed himself without any pretences at all was quite nauseating ... but, you see, the question would have been easier to answer if the man was still alive. He is gone and the new man seems to be dismantling the man's structures. I don't know whether I have answered your question.

No, we want you to assess the implications of Abacha's misadventure on the military, and on the country itself. And we have these layers of conspiracies, you have spoken about the power-play within the office of the head of junta, the ethnic dimensions and the implications of the oligarchy's continuing hold on to whoever is in power ...